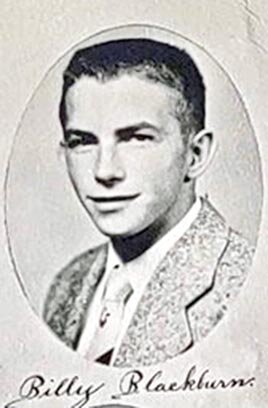

School Day Memories - Billy Joe “Bill” Blackburn

Billy Joe “Bill” Blackburn[/caption]

Billy Joe “Bill” Blackburn[/caption] GHS Class of 1956

by Nancy Hicks Williams

Special to The Enterprise

Born in the late 1930s on old Rte. #6 in Poplar Grove, near Dyer, Tennessee, Bill Blackburn grew up in the same house where his father was born: “It was an old four-square house, airish, cracks in the boards, open underneath. When those winter winds started howling, the linoleum rug started dancing. We could see the chickens under the house,” explained Bill in his soft, Southern drawl.

“Daddy’s folks always talked about in 1876 when Grandaddy (Samuel Rochester Blackburn) was a young boy, how those two nicely dressed riders came up, stayed the night, and kept their saddle bags mighty close. They ate, saddled up, and rode away, never to be seen again. Local legend has it that they were Frank and Jessie James.”

“My daddy, (Joe Horace Blackburn), bought a new 1941 Chevy for $900, and three days later, sold it for a $50 profit, thinking that was a good deal. Little did he know, WWII was about to break out and all the factories would be converted to manufacture wartime products, not cars. With the exception of a few 1942 models, no cars were manufactured from 1941-1946 in the U.S. My family did not have a car for five years. Mama (Oma Nell Brundige Blackburn) was not happy.”

Bill continued to explain that his grandmother, Mrs. Clercy Fowler Brundige, of Gleason became ill during this time frame, and tenderly spoke, “Mama did not get to see her for three years. We did not have a car and had no way to travel. She died in 1947. Daddy sure was feeling awful sorry about Mama.”

“That next year, he sold the cotton crop, took the $8,300 and bought a 100-acre farm in Gleason across from the Howard Ross place. We moved in January 1949.” Bill was ten years old, armed with his “cap pistol, bb gun, and all the birds, rabbits, and bullfrogs a boy could want.”

Bill’s sister, Etta Lea, went to live in town with their grandfather Pete Brundige so she could attend city school. Bill and brother Bobby attended East Grove School out in the country, but for one day only. School Master Verne Jennings spanked young Billy hard for making a funny sound while coming in from recess.

Day two, the brothers tried Shady Grove School instead: “There stood this little lady in her plain gingham dress, white hair up in a bun, among eight rows of desks, teaching all subjects to all grades by herself.” Mrs. Cordie Verdell became Bill’s favorite teacher of all time. “She had a lovely personality, always positive, encouraging, smiling, a compassionate demeanor, and loved everybody. Mrs. Cordie had to relocate, but I never forgot her.”

Billy and Bobby got up at 4:00 AM to start their daily chores before school. They hand-milked 25 dairy cattle every morning and night. Bill always marveled how the same six cows would go to the same six milking stations, in the same rotations, daily. They then fed the hogs, had a big homecooked country breakfast, dressed, and walked three miles to Shady Grove School.

Miss Lucille Dunn (Lomax), their next teacher, paid them ten cents each, per week, to arrive an hour early, gather the kindling, fill a bucket of coal, and start a fire in the pot-bellied stove. They tossed a baseball around in the empty second room until their classmates arrived.

“Miss Lucille brought a load of kids from Gleason to our country school every day to keep the average daily attendance at 15, or the school would close. Billy Ward was one of them. He could read and write. I know. I was there. He just didn’t want to.”

Bill’s favorite subjects were history and math. He read and memorized his little green Tennessee History book every night before going to sleep. Mathematics taught him to take a situation, concentrate, multi-task, and explore anything that might happen. English grammar was a “thorn” in Bill’s side that he “didn’t need to know.” However, Bill adds “I learned differently, differences in how one gets promoted ... being an effective liaison.”

“Daddy always told me and my brother Bobby, ’Do your best.’ Well, we did. Time meant nothing. We worked all day,” Bill said proudly, and continued, “Now, Bobby, he was smart, real smart, but not a farmer. Picking cotton ... herding hogs, Bobby’s watching birds. Daddy never raised his voice, never fussed at us. We always got the jobs done. Bobby was destined to do other things. I loved my brother.”

After their farm was “laid by,” the Blackburn brothers would go work for other farmers, usually hauling hay. “Whatever they would pay us was more than we had.” The boys also trapped, gutted, and sold rabbits, killed bullfrogs for Mama to fry, and attended all summertime revivals. “Daddy would take us on day trips to the Memphis Zoo and Shiloh National Park.”

With the 50s, Bill remembers new technology setting in: electricity, a mighty fine refrigerator, catalogue ordering from Montgomery Ward, a new tractor, and a cream separator, ranked as #1 in the “Top Ten Money/Time Savers” for farmers.

Bill would pour the milk into a three-gallon tub set up above the machine and turn the wheel. Skim milk would pour down one spout, cream, the other. Bill took the fresh cream to his grandfather’s Gleason Produce House, to a window at the back corner where Ruby Phelps (John David Phelps’ mother) would buy the cream, ice it down, and ship it on the 5:00 PM train to Chicago. That boarded-up window can still be seen at the back of Horn’s Hardware.

Bill graduated GHS in 1956, an era of Elvis, Carl Perkins, and flat tops. Bill was honored as GHS Football’s “Best Lineman” and “Best Blocker.” Though he had a high school sweetheart and was part of the “best bunch of guys to hang out with,” Bill remembered, “I was basically a loner. My brother was my running mate.” His brother Bobby tragically died at just 37 years old in a forklift rollover accident.

Duty to his country took Bill to Ft. Jackson. After the military, glass-packed mufflers and spinner hubcaps carried Bill to Memphis and Beale Street, where he styled himself at Lansky’s. At the advent of the Computer Age, Bill attended the Punch Card Trade School there in 1961. Valued for his design and innovation, Bill exceled in his thirty-year career as a computer super programmer, “a long way from ten cents a week,” he mused.

Bill has a son, daughter, and three grandchildren.